My last article focused on weighted balls and the benefits in which they can have for a throwing athlete. Since weighted balls are a type of overload training I thought that my focus this week should involve the overload principle.

The overload principle is defined as the application of any demand or resistance that is greater than those levels normally encountered in daily life. The body is quite amazing as it has the ability to adjust to the demands of physical stress placed upon it. When you stress the body in a manner it's unaccustomed to, the body will react by causing physiological changes in order to handle the stress in a better way the next time it occurs.

The most well known example of overload training takes place in the weight room. Athletes perform movements with added weight and this overload creates physiological changes in the body such as increased muscle strength and size. The problem with most weight room lifts is that the athlete is moving a tremend ous amount of weight through a short, restricted movement and at a very slow rate of speed. While this may help offensive lineman in the NFL, it does not make much sense for baseball players (or most other athletes for that matter). Athletes have specific movements which they must repeat over and over during the course of a game. One of the most effective ways to strengthen and prepare for these sport specific movements is by utilizing the overload principle. For example, like I mentioned in my last article, throwing weighted balls is a type of overload training. When you place the additional stress of the extra weight of these balls on the arm and shoulder the body will adjust to this new demand. It adjusts by creating a new arm action which is more efficient and places less stress on the arm/body. This is obviously a benefit to a throwing athlete but is not the only one. The added weight also will help to strengthen the arm and shoulder since there is additional weight being thrown. This strengthening will also help to protect the arm from injury once you drop back to a 5 oz baseball.

Overload training can also be used in hitting. Everybody has seen batters who are on deck add donuts or bat weights to their bat when warming up. A hitter can use differently weighted bats to strengthen his swing and to prepare the muscles used during the swing for the stress of the activity. I suggest that in order to get the most out of overload training with heavier bats that the weight not be dramatically heavier than the one used during a game because the object is to make the swing as game like as possible. This is best accomplished by measuring bat swing speed and to constantly try to improve swing speed with each of the heavier bats (just like you would measure the velocity when throwing weighted balls).

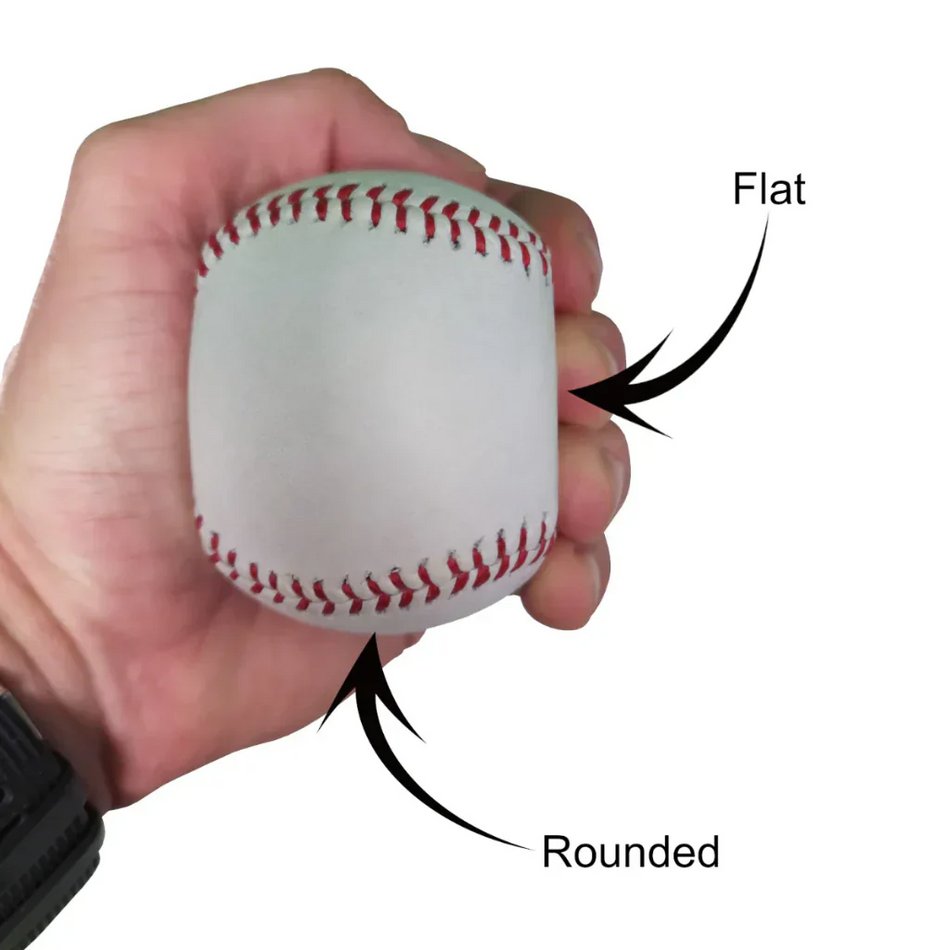

Another way to train hitting via the overload principle is to hit weighted balls. This is essentially overload training at contact point. By hitting balls which are heavier than the baseball which you normally hit, it will force your forearms and hands to become stronger at the most important point of the swing. Often times a hitter, especially a young or muscularly undeveloped hitter, is unable to keep driving the bat through the ball at contact. It looks as though the bat rebounds backward when contact is made. Working on impact training with weighted balls can help translate into hitters driving the ball further.

Overload training doesn't solely pertain to increasing the weight during the exercise. It can also mean a higher work load in the form of more reps and longer distance. One example of this is long tossing. Many of us are familiar with the long toss programs of Alan Jaeger and Ron Wolforth, who promote long tossing for 30-40 minutes while stretching it out as far as you can throw. This forces the body to find new ways to throw the ball longer than ever before which often creates more energy throughout the throw, more efficient arm actions, and a stronger, more durable arm. This type of long toss program puts more "stress" on the arm in two ways: Increased distance than normal and more throws than usual.

Many people may not like the term "stress" but that is exactly what you must place upon the body in order to get better results. There is constantly stress on your body whether you are walking, running, or playing a sport. The purpose of placing additional stress on the body is to prepare it for the usual stress that accompanies what you do when playing your sport.

Overload training can also take place in speed and conditioning training. Equipment such as running parachutes, partner tow and release, bungee cords, and resisted running flat bands to name a few. All of these devices allow for an athlete to train as they normally would yet with added resistance which forces their muscles to move more weight than normal thereby strengthening them. Whether the athlete is looking to improve speed, power, explosiveness, or their running form all of these things can help accomplish that goal while not changing the training exercises.

The best thing about overload training such as I have mentioned is that the athlete is able to train his body and the specific muscles used during game situations by adding resistance to sport specific movements. Not only is the athlete able to train through the same range of motions but also closer to game speed even with the additional weight. This is far superior to overload training involving random, slow movements in a weight room that an athlete will most probably never perform during competition. Overload training helps prepare your body for competition since it has had to consistently deal with far more stress than it will during actual games. It also helps to improve performance since your body naturally responds to this additional load, creating more efficient and stronger movement patterns. Most of us already do overload training to some capacity, I just encourage you to re-evaluate how you are using it and try to make it as game like as possible. Next time I will be discussing underload training and what its benefits consist of.

Until next time,

Brian Oates