My last blog was on the subject of pronation and how it is the body’s natural way to slow down the arm after a throw as well as its way to help dissipate the tremendous amount of energy and stress created during the throwing motion. Pronation is one of the best ways to help keep a throwing athlete, especially a pitcher, healthy and able to continue answering the bell week after week.

(Photo courtesy of https://www.chron.com/sports/astros/article/Roy-Oswalt-says-Astros-have-potential-for-dynasty-13287149.php)

Although pronation is natural, not every thrower does it very well or very efficiently. Like I mentioned in my last post, the heavier an object the more your body naturally calls for you to pronate to help disperse the stress caused by this weighted implement. With a heavy ball such as a shotput or football the brain realizes that in order to protect the body from injury, which is its top priority, it must overemphasize its natural method for dissolving the energy of the activity. If too much energy, a.k.a. stress, is placed upon one muscle, tendon, or ligament, then a serious injury can occur, such as a U.C.L. tear (Tommy John surgery) or torn labrum.

The problem with throwing a baseball stems from how little the ball weighs. Because a baseball only weighs 5 oz the body does not perceive it to be a serious concern in terms of the stress it will place on the arm. This is problematic because now you have a weighted instrument which is light enough that the body does not place as much importance slowing the arm down coupled with the fact that the arm speed involved in throwing a baseball is increased over that of throwing a heavier object. This is what causes pitchers to break down time and time again more than any other throwing athlete.

This being said, it is possible to train a pitcher (or any baseball player) to improve pronation. By improving pronation I mean the pitcher is pronating sooner after release and is able to continue and hold this pronation throughout the entire follow through. Let me first explain what I mean by holding pronation throughout the follow through. Most pitchers pronate after release and are on their way to dispersing the energy safely throughout their body. But after release as the pitcher begins to come over his front leg in the follow through is where many pitchers encounter problems.

In order to continue the deceleration process safely and to keep the stress off of the elbow and rotator cuff, a pitcher needs to continue to rotate over his landing leg. This involves both coming over his front leg home plate as well as rotating over this leg toward first base. The old timers called this “showing your number to the catcher,” implying they would rotate enough that the catcher could see the number on their back. I’ve also heard people say they try to have their shoulder blade facing the catcher.

(Photo Credit: https://www.si.com/mlb/2012/06/14/classic-photos-cliff-lee) (Photo Credit: https://www.minorleagueball.com/2013/7/15/4524910/prospect-retrospective-tim-lincecum-rhp-san-francisco-giants)

This movement allows you to keep your trunk moving along with your arm, helping to slow it down gradually. Ideally, you want your hand to stay in the middle of your body never extending out across it. As you can see in this picture on the right with multiple images of Lincecum, his arm stays in front of his body at all times. Cliff Lee on the left here has rotated so much that his shoulder blade/number are facing the catcher. The reason that some pitchers’ arms fling across their body out by their hip or even further is because their trunk stops moving. If the flexion and rotation of the trunk stops before the arm has finished decelerating, then the arm will straighten out across the body causing the “banging out on your elbow and/or shoulder.” I heard Coach Wolforth comment that this is similar to being in a moving car with your seat belt on that suddenly has a head on collision. Because the seat belt is stopping your trunk from moving all the energy is forced into your neck and your head flings forward, the result being whip lash. If you were only wearing a seat belt across your lap (not across the lap and shoulder) then your entire trunk would come forward spreading the energy across your upper body and would therefore save your neck the trauma of whip lash (this is hypothetical of course since you would most likely find the dashboard with your face). This is similar to what we are trying to prevent with pronation and flexion/rotation of the trunk, keep your upper body moving so you don’t experience whip lash in your arm. Check out how upright this pitcher for the Padres is compared with Cliff Lee above. His trunk stopped moving far earlier than Lee causing his arm to extend out.

(Photo Credit: https://bleacherreport.com/articles/611749-padre-pitching-staff-2011-can-they-duplicate-2010)

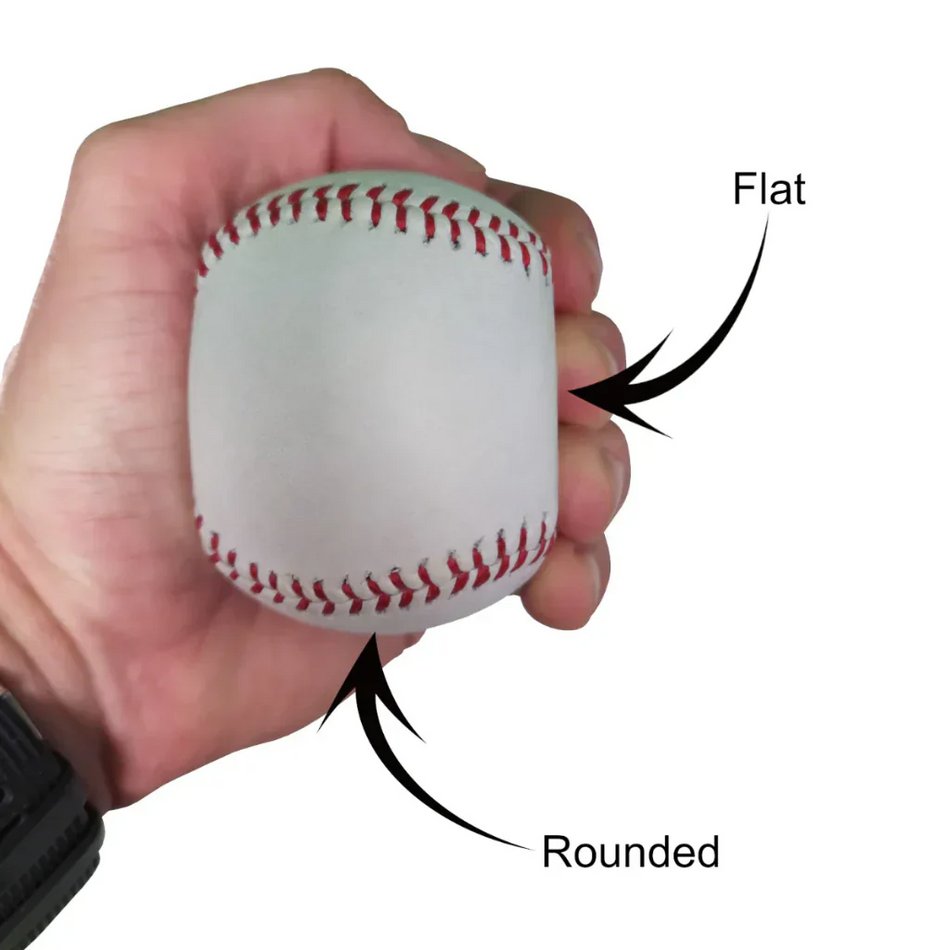

As I have previously mentioned, athletes at the Texas Baseball Ranch are training to increase pronation during their throws. Coach Wolforth has implemented a throwing drill in which he is blending pronation into a pitcher’s throw. Earlier I talked about how it is easier to pronate when throwing heavier balls than light because the body naturally wants the stress of the ball/object to be spread throughout the larger muscles in the back. Because of this, it is easier to teach a throwing athlete what pronation feels like by having them throw weighted balls. At the ranch an athlete takes a 4lb, 2lb, 21oz, 14oz, 7 oz, and a 5 oz baseball and throws them in progression from heaviest to lightest.

The athlete is on one knee with this knee being on an incline board (the incline board is turned to where its highest point is closest to the target). The athlete spreads out his legs and focuses on a short tight arm action, without turning/torquing, and then throws it at the target concentrating on two things: 1.) Pronating as soon as they release 2.) Rotating as far as they can over and around that front leg. During this drill the thrower stays on one knee and does not come to a standing position after they throw. It looks similar to a final arc drill except it is done on one knee.

The progression from the heaviest ball to lightest is critical because as the athlete throws the 4lb and 2lb balls they will naturally pronate the most, therefore their body can get a feel for what it’s like. The thrower then works down to a baseball each time trying to keep the feel of pronation that they had with the previous heavier ball. Eventually the athlete will even throw a 4 oz underload ball, with the ideal being if they can pronate and keep rotating with this ball then they won’t have a problem doing it with a heavier baseball. All indications from the Texas Baseball Ranch are that this drill has done a miraculous job teaching pronation and rotation during the finish. Many of the extremely hard throwers who train there love this drill as they say it seems to take all the stress off their arm, keeping them fresh and helping them to recover more quickly.

If a pitcher can keep his arm from “banging out” or jarring during the throwing motion then the chances of that pitcher staying healthy is increased tremendously. Notice the pictures of pitchers who I have added in this post are pronating after release, rotating until their arm stops, and their arm never locks out always staying in the center of their body. These are also pitchers who have a history of being durable and arm injury free.

(Photo Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Johan_Santana_releasing_a_pitch_in_May_2008.jpg)

(Photo Credit: https://apnews.com/article/kate-upton-ap-top-news-baseball-houston-north-america-c488458c2a1c46e2ba522864be0157c0)

If you have any questions or comments about pronation, the drill to help with pronation, or anything else don’t hesitate to contact me.

Until next time,

Brian Oates

Brian@Oatesspecialties.com