Last year I wrote two articles regarding pronation and the deceleration process of the arm after a pitch is thrown. For those of you who have not read those articles, I will give a brief recap. As many of us now know, pronation is a naturally occurring process. Something that our bodies do innately in order to protect the arm as it has to travel from its peak arm speed at the end of the acceleration process to a dead stop in an extremely short period of time. Baseball athletes, specifically pitchers, endure the worst epidemic of arm injuries of any overhand athlete, and it is common to hear announcers, commentators, and writers discuss what can be done to stop these injuries.

Unfortunately, too many of these individuals – some of whom were great pitchers themselves – incorrectly believe the key to protecting an athlete’s arm from injury is to put him on a restrictive pitch count along with a mandatory number of rest days between outings. This type of solution for addressing arm injuries is akin to putting a band-aid on top of a gushing wound – it might slow down the bleeding, but it will never heal the wound. Or for those of you who like analogies as much as I do, it is like trying to fix a bad set of car brakes by suggesting to the driver to drive less, therefore, you won’t have to deal with the possible dangers associated with having a worn out set of brake pads.

The car brakes example is especially useful for this discussion because your arm can easily be compared to a car – a pitcher’s ability to accelerate his arm is like the car engine, while the deceleration of the arm after release is similar to brakes. The problem with many pitchers is they have good engines matched together with bad brakes. The ability to throw hard only requires that an athlete be able to accelerate his arm from the time he separates the ball from his glove to release. But the ability to repeatedly perform this acceleration process and continue throwing hard day after day requires a good set of brakes to protect the “engine.” Many articles, suggestions, and workouts can be written about the acceleration process to help an athlete find increased velocity, and most coaches spend far more time developing this part of their pitchers’ delivery than the deceleration process. This is the case because most coaches, players, and parents are primarily concerned with velocity. Nearly everybody in baseball is obsessed with that magic number – 90 miles per hour. And this is for good reason, as it will help pitchers get recruited to top schools and scouted for professional baseball.

But it is a disservice for coaches to simply focus on acceleration. You are only increasing the chance your pitchers will get hurt by placing more emphasis on acceleration without any time spent for deceleration. Yet, this is exactly what 99% of coaches, trainers, and players focus on. But those athletes who are training at the Texas Baseball Ranch are in the 1%. Coach Ron Wolforth, probably best known for his weighted ball and velocity enhancement training routines, has put together a series of drills that specifically train pronation.

As I have mentioned in those previous blogs, pronation is a naturally occurring process, but because a baseball is so light and the arm is traveling at such a high speed, the body needs to be trained so that it can pronate as early as possible. Pronation should begin to occur the moment that the baseball is released from the hand. Many pitchers don’t pronate until well after the ball has left the hand, and in fact, there are some who don’t pronate at all. By pronating as early as possible, the arm will not straighten out at the elbow, preventing the banging that often occurs, especially after breaking balls.

But pronating with the arm is not the only movement an athlete should be focused on. Once the pitcher releases the ball and begins to pronate, he must also continue rotating over his front side. The pitcher’s trunk must keep rotating both forward over the landing leg knee and also around it so that the arm has more of an opportunity to decelerate while tension free. If the trunk stops rotating then the arm, which is still traveling at a high rate of speed, will be forced to slow down on its own, and the only way it can accomplish this is by straightening out across the body causing a banging to occur at both the elbow and shoulder.

With these two thoughts in mind: pronation as early as possible at release and continued trunk rotation, Coach Wolforth created the pronation drills. The equipment needed for this drill is a pronation bench, a set of extreme duty weighted balls, and an oval balance pad.

The athlete should spread his legs out wide (uncomfortably wide) to mimic his stride and then place his back knee on the balance pad, which is secured to the pronation bench. The pronation bench is angled to allow the athlete to adjust up or down the height at which his knee is resting depending on how tall he is. The first action the athlete should take is to simply bow his arm and upper body back into a type of “scap load” position while in a semi-torque. Remember: this is not an arm action/acceleration drill, it is a deceleration drill – therefore, we are concerned with what happens after release not before. Next, the athlete rotates and fires the ball toward the screen/net with the focus on pronating as much and as soon as possible. The athlete stays on one knee while allowing the arm to slow down via pronation and the throwing elbow should elevate above the pronated hand.

As the athlete rotates and his hand/arm near the landing leg/knee the athlete must continue to rotate over and around that leg. This ensures that the trunk of the body is helping to decelerate the arm and that the arm does not ever straighten out. A good goal to aim for is to never allow the hand to wind up across the belly button. If a pitcher rotates enough this will not be a problem. It only happens when the trunk stops rotating and the arm is forced to straighten out.

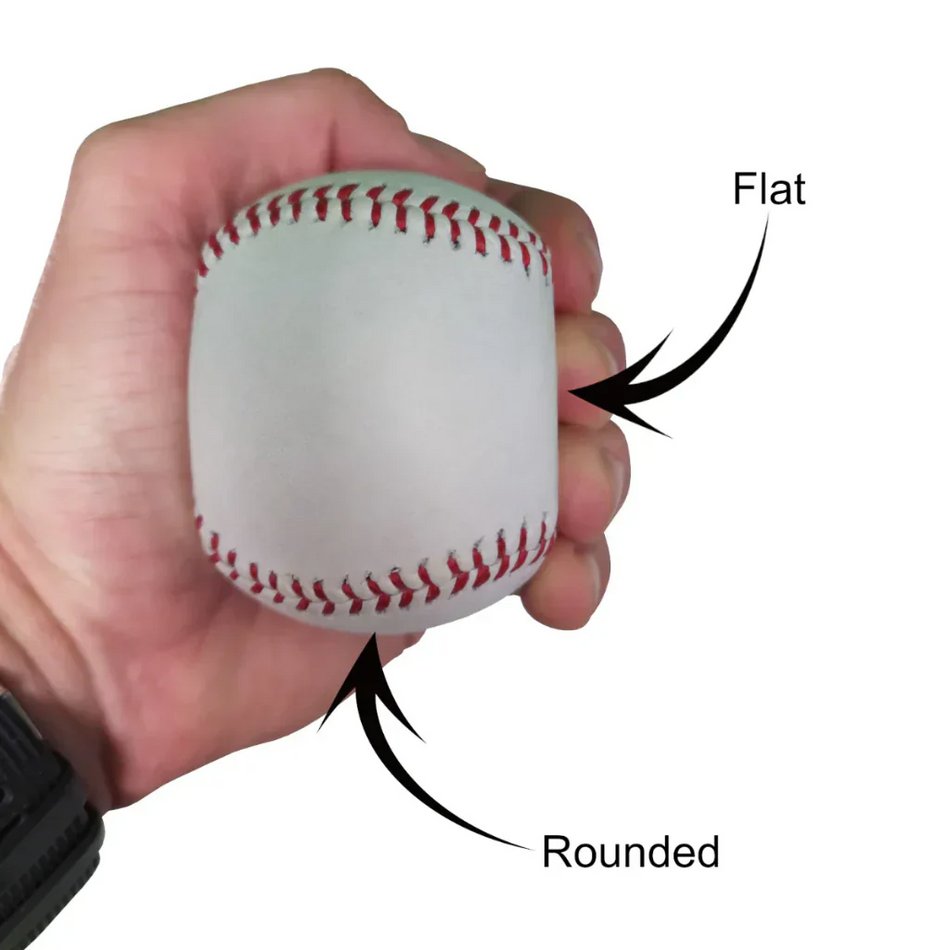

The first set of drills are performed while remaining with one knee on the pronation bench, but the second set or “pronation 2” requires the athlete to actually come over his front leg very similar to a pitch. This forces the athlete to simulate his pitching follow through as the back leg comes over and through so the pitcher can get the feeling of rotating over his front side. As I mentioned previously, the pitcher uses the set of extreme duty weighted balls during the exercise. He begins with the 21 oz, then moves to the 14 oz, the 7 oz, the 5 oz, and ends with the 3.5 oz underload. The reason for this is that the heavier the ball, the easier it is to pronate. This is why quarterbacks, shotputters, javelin throwers, and other overhand athletes don’t get hurt as often – the body realizes how heavy the object is and wants to do as much as it can to protect the body, which forces an early pronation. As the pitcher moves to the lighter balls, the task of pronating and never letting the arm straighten out gets more difficult, partly because the arm speed increases and in part because the brain doesn’t sense it is as necessary as with the heavier balls. The 3.5 oz underload is the last ball in the series because if an athlete can pronate and properly decelerate his arm with this light of a ball, he will be able to do it with the heavier baseball.

The athletes who train with Coach Wolforth begin each day warming up with these pronation drills and it really pays off. I was extremely impressed with how well many of the regulars were able to decelerate their arms and how effortless it looked. I would seriously recommend everybody to begin some type of pronation drills as soon as possible, especially those who regularly have arm pain and soreness because this could be the solution to your problems.

Until next time, Brian Oates

Brian@Oatesspecialties.com